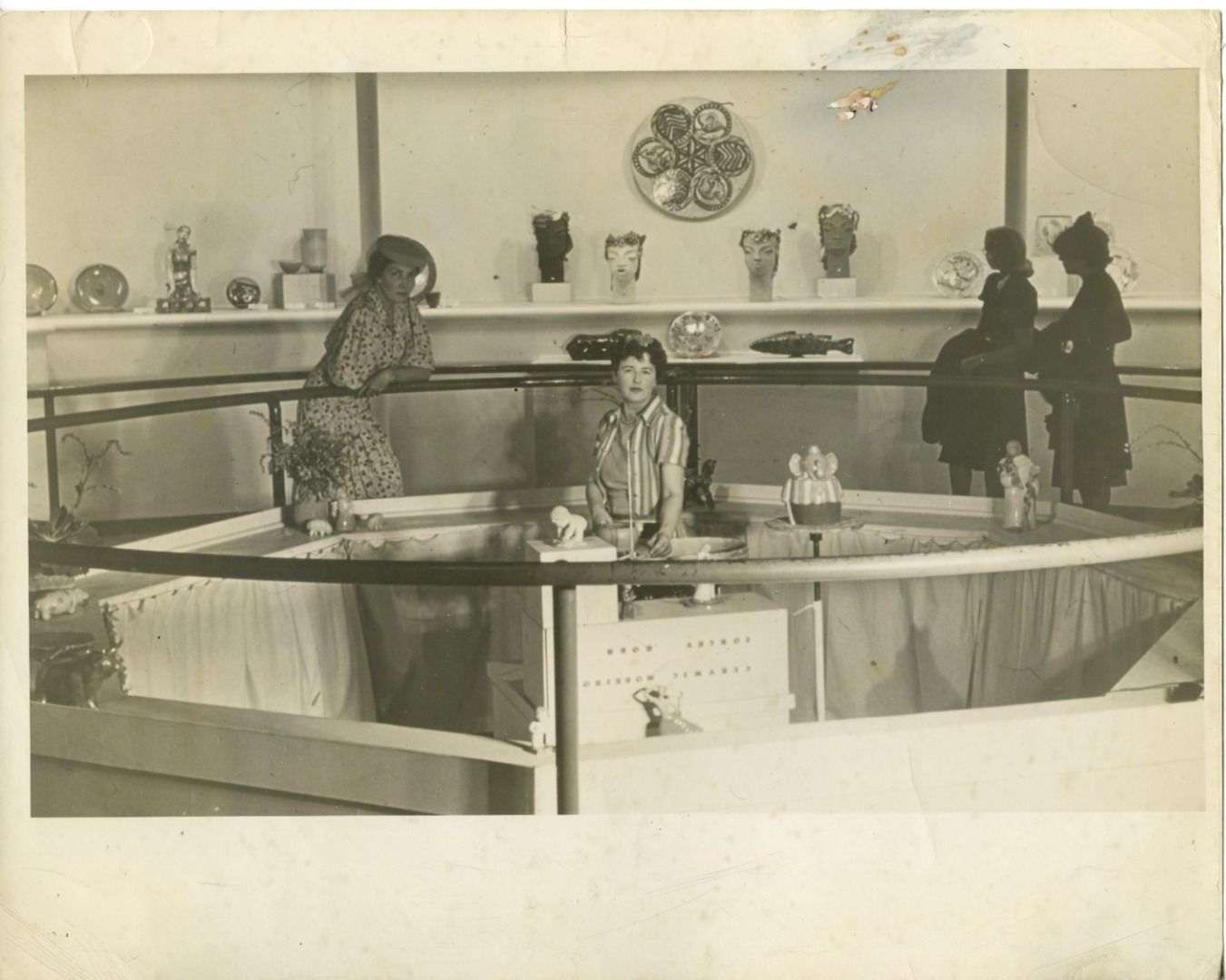

A few weeks ago, we shared a blog post about a painting by Beatrice Wose-Smith in the collection of the Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts that was included in the Golden Gate International Exposition. This was just one example of the Syracuse Museum’s (today the Everson Museum of Art) involvement in the 1939 San Francisco World’s Fair. The Golden Gate International Exposition had five divisions within the department of fine arts: European Art, Decorative Arts, American Art, Pacific Cultures, and Education. While the Syracuse Museum’s Wose-Smith painting was shown within the context of the American Art division, the Museum played a far bigger role in the fair’s Decorative Arts division. Dorothy Wright Liebes, a prominent weaver and textile designer, served as the fair’s Director of the Division of Decorative Arts. In this role, she was responsible for all decisions regarding the procurement and display of art objects categorized as decorative: everything from interior design to bookbinding and illustration, from textile weaving to jewelry making, and even ceramics. In March 1938, Syracuse Museum Director Anna Olmsted wrote to Liebes with a proposition. Instead of Liebes organizing an independent exhibition of American ceramics for the fair, Olmsted suggested that the Syracuse Museum send a significant portion of its Seventh Ceramic National exhibition to the fair instead, “to serve as the nucleus for your exposition of ceramics.” This was a brilliant play on Olmsted’s part; the Syracuse Museum was already experienced in sending its Ceramic National exhibitions on tour, both nationally and internationally, but could not travel the exhibitions to the west coast every year due to the great demand for the exhibitions in the eastern half of the country. By securing a west coast venue, particularly one as large as a World’s Fair, the Syracuse Museum would reach a sizeable new audience. Olmsted also recognized that two competing national ceramic exhibitions in the same year would likely result in important artist omissions from each. It was even possible that the fair would upstage the Syracuse Museum’s Ceramic National, something Olmsted could not abide. Her proposal to Liebes had the potential to solve both of these problems. Liebes responded enthusiastically to Olmsted’s letter, praising her work on behalf of the ceramic arts and happily accepting the proposal to exhibit a portion of the Seventh Ceramic National at the fair. Liebes also outlined her planned program for the Decorative Arts division, which included workshop components where artists created work within the galleries themselves, providing spectators the opportunity to see artists in action. The above photograph shows artist Sorcha Boru positioned to give a ceramic demonstration in the gallery. Liebes leans against the railing to Boru’s right. Ultimately, the Syracuse Museum lent more than seventy ceramics to the fair, including many works in the Museum’s collection today, such as Waylande Gregory’s Europa and the Bull, Ruth Hunie Randall’s Winter Weasel, and Arthur Eugene Baggs’ Cookie Jar. Other ceramics borrowed from artists, museums, and collectors around the country were displayed side-by-side with the ceramics from the Syracuse Museum. To view the full correspondence between Olmsted and Liebes, as well as other documents associated with the Syracuse Museum and the Golden Gate International Exposition, visit the Everson’s Ceramic National Exhibition Archive.

-Steffi Chappell, Assistant Curator