For kids grappling with the pandemic’s traumas, art classes can be an oasis

Drama, music, dance and other art classes allow kids to tap into their 'creative superpowers,' says Rolling, who is also the Chair of Art Education at Syracuse University.

Article Excerpt:

School’s a little different this year, so art teachers are using their classes to help kids cope.

After spending months trying to get used to remote learning, now kids are struggling to adjust to being in school in person again. Health experts recently declared the decline in children and adolescents’ mental health a “national emergency.” As schools grapple with the social and emotional effects of the pandemic on students, music, theater and other art teachers are trying to help.

Going back to school means big transitions

Imagine you’re back in sixth grade, your first year of middle school, surrounded by tons of new people you don’t know. It’s a big transition for kids, says Jesse Mazur, the principal of George Washington Middle School in Alexandria, Va.

“We have sixth-graders that come from eight different feeder schools, so when our sixth-graders arrive here, there’s generally some jockeying for social positioning.”

This year, says Mazur, there’s so much jockeying going on, “it’s almost like we have an entire building full of sixth-graders. … I think it caught us all off guard. The student behaviors were not what we anticipated. Coming back together, resocialization required more support than I think we were ready to provide.”

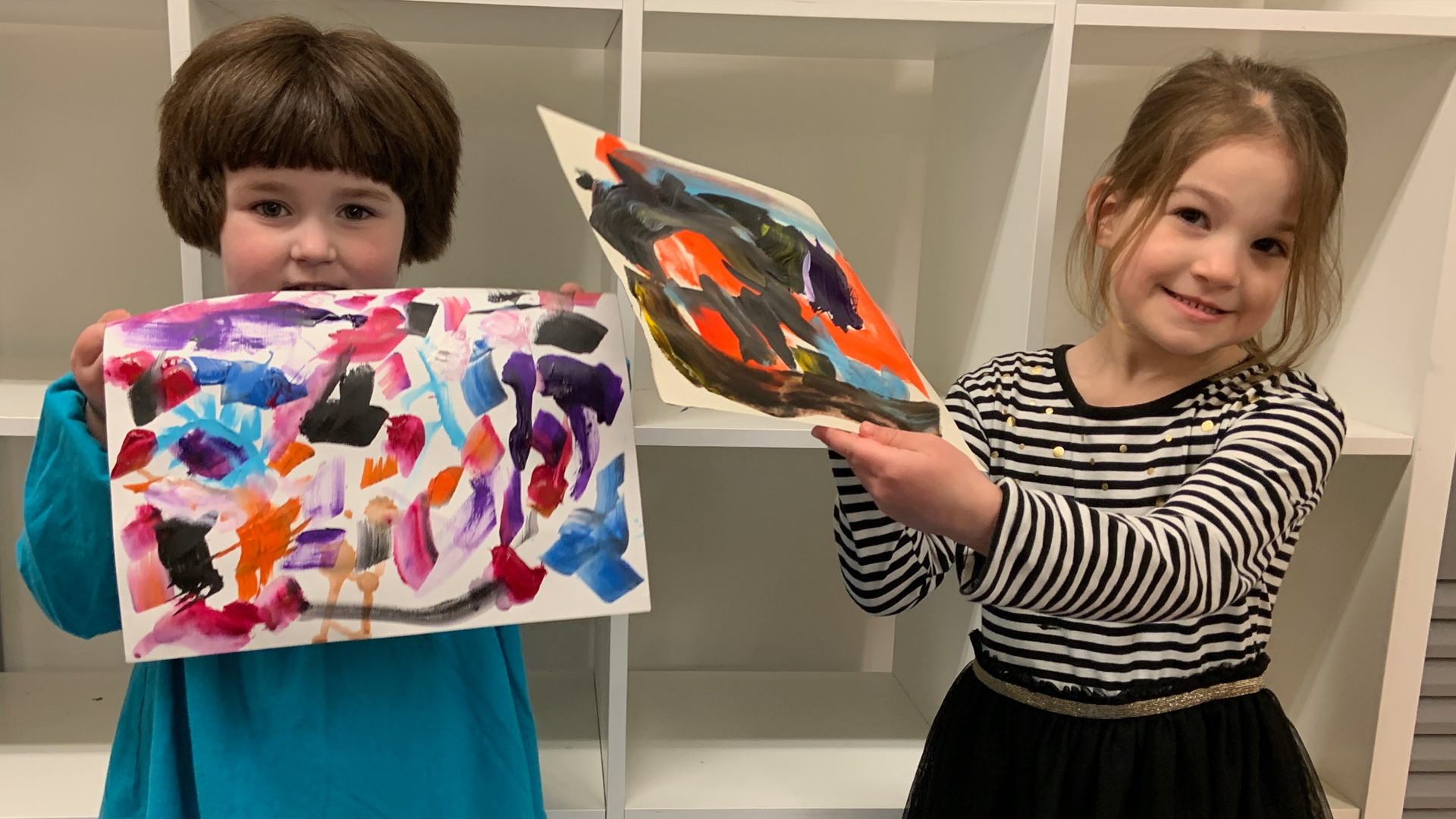

Art is a way to channel big emotions

Emotions are the stuff of great theater. Robert McDonough’s drama class at George Washington is controlled chaos as some 20 seventh-graders in small groups rehearse different scenes in the same room at the same time.

The energy, not to mention the noise, is high, and McDonough doesn’t try to turn it off. Amid the constant chatter, each group takes its turn performing for him. His feedback is enthusiastic but pointed: “Memorize your lines” and “Wait for her cue.”

After months of being “estranged” from their peers, McDonough says students are eager to be together again. “There is a hunger for that piece that was missing, and so they’re on the search to find it, to get it, and it’s great,” he says. “It can also be a little tiring,” McDonough laughs.

James Haywood Rolling Jr., a former art teacher and president of the National Art Education Association, hopes art teachers recognize that “even though it’s a struggle right now, we’re very much needed.”

Drama, music, dance and other art classes allow kids to tap into their “creative superpowers,” says Rolling, who is also the Chair of Art Education at Syracuse University. He says art class is often a school’s “oasis.”

“Art teachers have a unique ability to affect students’ agency, the sense of being able to take what is a mess or chaos and make order out of it,” says Rolling, “even if one is feeling lost in oneself or in the context of one’s daily circumstances, we have this ability to get at that thing that makes us human.”

But Rolling acknowledges it’s not as though kids can just go back to art or drama and suddenly everything’s fine, especially when teachers themselves are feeling the stress.

Early childhood music teachers, for example, have had some of their most effective teaching tools taken away, starting with the most popular: singing.

Music teachers are improvising

At Frances Fuchs Early Childhood Learning Center in Prince George’s County, Md., music therapist Monica Levin keeps her sessions safe by Zooming into small classes, even though she’s in the same building. A group of five kids are masked up and keeping their distance … for the most part — they’re 3- and 4-year-olds. Levin easily gets them singing and dancing.

While this might be better than no music class at all, Levin says the pandemic has limited what the kids can do.

“They’re missing the ability to share, to take turns, to touch toys together … to work together in a group,” says Levin. Pre-pandemic, “I could sit kids on the floor and they could share a small drum together, so they’re making music together.”

Another popular activity had the kids “build a tower out of instruments and then pretend they were something else.” Levin says she misses that kind of creative play, “because it’s a catalyst for language development, questions and answers, inquiry.”

Songs can be a powerful instructional tool. Music therapist Stephanie Leavell says she’s written dozens of pandemic-themed songs for young children including “The Masked Moose” and “The Washing Walrus.” She’s been sharing them with music educators around the country.

Leavell says she never sugar-coats her lyrics.

“Kids are so perceptive,” she says, “They have the ability to understand their own emotions in the right environment, so I like creating songs that really acknowledge those real emotions and big emotions that kids have.”

The song “School’s a Little Different This Year,” for example, “was just an opportunity to say, you know, all of these big things are happening, all of these big changes are happening, but it’s going to be OK,” Leavell explains.

Teen angst is heightened

Older kids are also wrestling with real pandemic-induced emotions. Interacting with peers is an essential part of teens’ social development.

According to Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health, “the pandemic’s shrinking of their world has been especially difficult.”

“Since we’ve been alone for over a year, getting back into socializing with classmates and teachers,” says Heaven Hill, a high school junior in Chicago, “I have noticed, like, a disconnect. Being around so many people at once, I can feel kind of anxious sometimes.”

For Hill, making art is an important outlet. At a program called After School Matters, she and other students and artists collaborate to make brilliantly colored mosaics that have been turned into public murals.

“Each person kind of gets their own section to work on,” says Hill, “As we go, we start putting the pieces together…it’s basically just like one big puzzle and we all put it together at the end.”

The process of solving the puzzle and figuring out “how I can make these tiles flow and show movement through tile and color,” says Hill, is “a great creative way to say what you want without actually having to speak.”

There’s another side effect of art-making.

Whether it’s a mosaic, writing a poem or learning to play an instrument, making art is about solving problems. “That ability to make something from nothing,” says James Haywood Rolling Jr., also builds “resilience.”

James Haywood Rolling Jr. is Dual Professor of Arts Education and Teaching & Leadership in Syracuse University’s College of Visual & Performing Arts (VPA) and School of Education, and he has served as Chair of the university’s Arts Education programs since 2007. Rolling is also an affiliated faculty member in African American Studies. From 2018 to 2020, Rolling was appointed to serve as the inaugural Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for VPA. Dr. Rolling will begin his term as the 37th President of the National Art Education Association (NAEA) in 2021. Nationally, Dr. Rolling champions the cause of achieving greater diversity throughout the visual arts fields and is devoted to telling the story of how human beings creatively constitute, shape, and reinterpret personal and collective identity.