At the launch of their residency with the Everson Museum of Art last summer, social practice artists Amanda Leigh Evans and Tia Kramer set aside a week to contemplate how a day in their lives would unfold without any clocks in sight—whether it be worn on one’s wrist, hung on the wall, or displayed on a phone or computer.

“During that week we did a lot of writing and dreaming and scheming and testing,” Evans said.

Being a professor at Whitman College, in Walla Walla, Washington, Evans said she imagined she would need to intuitively determine when classes were about to begin and end, by observing the number of students who’ve arrived and when they start to anxiously pack up their belongings at the end of the period.

“There’s kind of a tyranny of the clock in a way—it’s a tool that we all use,” Evans said. “You could probably go a week without a cell phone, and it would be uncomfortable, but going without a clock—it’s nearly impossible.”

Artists-in-Residence Evans and Kramer are exploring the subject of timekeeping through a collaborative, socially engaged project which engages diverse partnering communities in Central New York. Made possible with a grant awarded by the National Endowment for the Arts, the artists will complete their residency—comprised of a multitude of remote research and two Everson visits aligning with equinox moments—on June 6, 2024, when community members, Museum staff, and the artists themselves will spend a day without a clock.

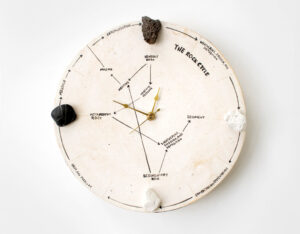

Though the project is still in its planning stages, the artists intend to work with collaborative partners in co-creating alternative time-keeping devices (in the form of ceramic objects and performances) that can be used to keep time at the Everson in replacement of a conventional clock. With Evans working primarily in ceramics and Kramer in performance art, the duo wanted to find a way to fuse these time-based mediums that engage with time in disparate ways.

Evans is an artist, educator, and cultivator who investigates social and ecological interdependence through artistic mediums like ceramic objects, gardens, books, websites, videos, sculptures, and long-term collaborative systems. Evans earned an MFA in Art and Social Practice from Portland State University and a Post-Baccalaureate in Ceramics from Cal State Long Beach.

Her work—rooted in research-based inquiry and long-term collaboration—often extends outside the bounds of a typical gallery space. Recently, Evans created a series of functional clock sculptures measuring geologic time, seasons, and the rotation of the earth, as part of the artist’s commitment to realize deep time through familiar devices.

Kramer, whose work touches upon everyday gestures of human connection, creates experiences that interrupt the ordinary and engage participants in poetry and collective imagination. The interdisciplinary artist, social choreographer, performer, and educator also holds an MFA in Art and Social Practice from Portland State University, as well as a Post-Baccalaureate in Fiber and Material Studies from the Art Institute of Chicago. In her recent project titled, For You and Us, Kramer devised a collection of performances for an audience of one including a final performance created for her mail carrier Phil, which was carried out with the collaborative participation of 87 residents living along his mail route.

Evans and Kramer—together known as Deep Time Collective—develop work that divulges how we understand ourselves in relation to time, place, community, and landscape. The Eastern Washington-based artists have been collaborating since fall 2021, the start of their multi-year project When the River Becomes a Cloud (Cuando el río se transforma en nube) as part of their residency at Prescott School in southeastern Washington State, near Walla Walla.

Prescott is a town of only 377 residents, and the PreK-12th grade public school has nearly the same number of students, roughly 80% of whom recently immigrated from Mexico or Central America, according to the artists. “There’s this mix of culture and language—and probably political values throughout the school,” Evans said.

When the River Becomes a Cloud (Cuando el río se transforma en nube) is a multi-year, collaborative public art project involving students, staff, and families of the Prescott School District. The developing partnership contemplates water as an analogy for how the school and its disparate communities function on a day-to-day basis. For example, like how water moves in cycles—evaporating from a liquid form into vapor, condensing into clouds, and eventually precipitating into rain or snow—students follow a weekly ritual of leaving home in the morning, attending school, and eventually returning home to their families again in the afternoon.

“Water is also an interesting theme to engage social emotional learning, while also thinking about migration and belonging,” Evans said. “And through the use of a big topic like water, we’re able to think through what it means to be living in the 21st century in relation to ecology, culture, and social structures.”

Similarly, the collective’s work with the Everson—which probes the concept of timekeeping—touches many of these larger concepts. Museumgoers and community partners who collaborate with Evans and Kramer in June will be invited to engage in a vitalizing conversation about science that touches upon their own background. Additionally, the project invites participants to reflect on the relationship between capitalism and colonialism and ways these structures have influenced our relationship with time.

Though time is universal to humankind, the way people delineate this quantity varies based on lived experiences. Evans and Kramer are approaching this project with the intention of guiding participants into a state of self-reflection, while simultaneously being mindful of how time molds communities at large.

“We’re thinking about how we can create access points into thinking about these things from a perspective that illuminates the interdependence that we have with each other, and invites the specificity of each person’s experience to be involved,” Kramer said.

The mix of time-keeping devices and performances that will be used to guide the day’s programming will be developed with a goal of establishing structures that will realistically support people to not rely on their clock, the artists said. A functional time-keeping device likely differs for a visitor browsing the galleries, a gallery attendant, or staff member working within the Museum’s administrative offices.

“Each individual experiences time differently,” Kramer said. “And when you look across the Everson’s staff there’s some varieties of comfort and discomfort that individuals have with this experience of going without a clock for a day.”

As visiting artists, Kramer and Evans aim to sustain the connections they are currently establishing in the CNY community by involving museum staffers who can preserve these relationships through future programming and outreach. Their programming disrupts traditional conventions of museum institutions and contemplates how it may cause people to think differently about institutions like the Everson, Evans said.

“We’re thinking about all of the systems that are involved or interacting with the Museum in order to make the day truly function,” Kramer said. “And that logistical challenge is also part of the conceptual beauty of the idea.”

Left: Tia Kramer

Above: When the River Becomes a Cloud

Right: Amanda Leigh Evans