The upcoming US presidential election, predicted to have important historical implications for the country’s political system, has reminded many citizens of the role they can play in shaping events larger than themselves. The race is anticipated to attract an unprecedented number of first-time voters, and citizens on both sides have flexed their political vocal cords in bigger and louder ways than in the past.

Civic Virtue: all over the floor brings together a disparate selection of artworks from the Everson’s collection that address the difficult, yet essential, role an active citizenry plays in a healthy democracy, whether through voting, volunteering, or protesting. The works broach a number of complex political subjects, including poverty, war, and human rights and range in era from the Great Depression to the Vietnam War. Some are activist pieces, making pointed criticisms of American policies or envisioning a better path forward, while others seek to crystallize the socio-political atmosphere of their time. The exhibition explores a broadening and blurring of the concept of civic virtue from the ideals of the founding fathers to those of 1970s activists.

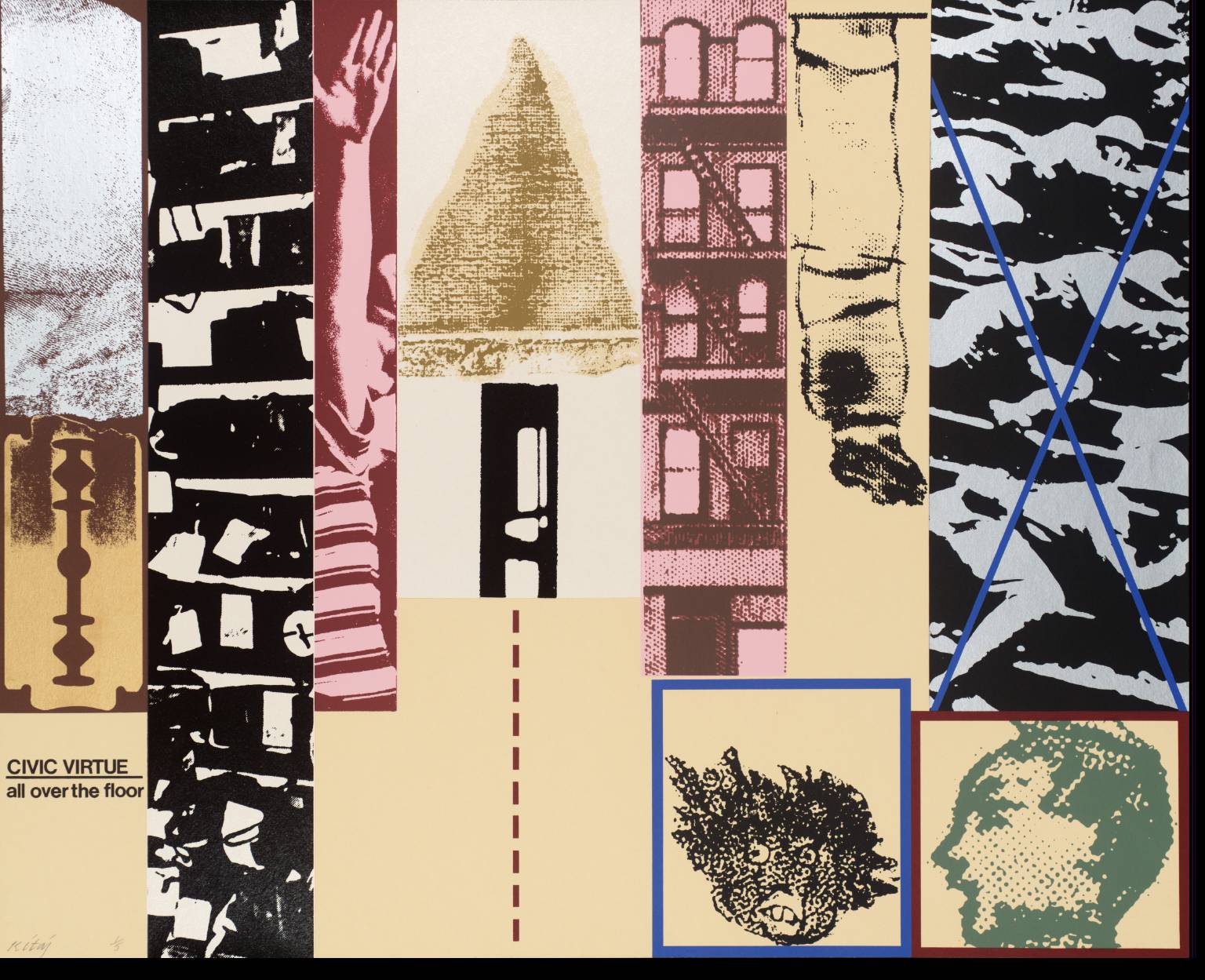

Titled after R.B. Kitaj’s 1967 print, Civic Virtue, which includes the phrase “all over the floor,” this exhibition focuses on the way artists have engaged with the confusing and often messy process of civic engagement. Kitaj’s method, using printmaking and collage, combines disparate visual elements that, like poetry, produce a myriad of interrelated meanings. Civic Virtue, 1967 acknowledges the ways in which the notion of civic engagement has changed in the modern era. During this period, civic morality became less certain as traditional notions of good citizenship and found new ways to engage, using activism as an instrument of civic virtue. This more ambiguous conception of civic morality contrasts with the classic patriotism depicted in revolutionary etchings like Allen Lewis’s The British Driven from Boston, 1932. The work portrays George Washington as a paragon of American virtue: a valiant soldier and champion of freedom. Civic Virtue: all over the floor explores the transition in American culture away from this classic idea of civic virtue depicted by Lewis, a transition that confused the relationships between violence, protest, and virtue.

Other works in the exhibition are themselves a form of civic engagement. Marisol’s Women’s Equality, 1975 is a statement of solidarity with the gender equality movement. In a portrait of women’s rights leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, Marisol draws her own hand reaching in, pointing toward the two women in a gesture of unity and shared legacy. Marisol, among other artists, expands the notion of civic virtue to include artistic expression, an act that empowers many not granted the rights to wield civic power in a traditional sense.

Many of the pieces in Civic Virtue: all over the floor continue to serve a civic purpose, acting as reminders of both American successes and failures. Walker Evans’ Depression-era photographs, like Political Poster; Plate VI, 1929-31, remain embedded in the American consciousness as visual artifacts of the period. The photo, portraying a solemn political poster of Herbert Hoover overlooking the tragic repercussions of the Depression, reminds viewers of their civic duty and the consequences if they don’t take their political responsibility seriously.

While democracy relies on the active engagement of its citizens, many overlook the various interpretations citizens may have of political activity. This exhibition seeks to broaden our understanding of civic engagement and explore the roles art and artists (and museums) have to play in political action.

R. B. Kitaj, Civic Virtue, 1967, screenprint, Gift of Dr. Edward Zucker