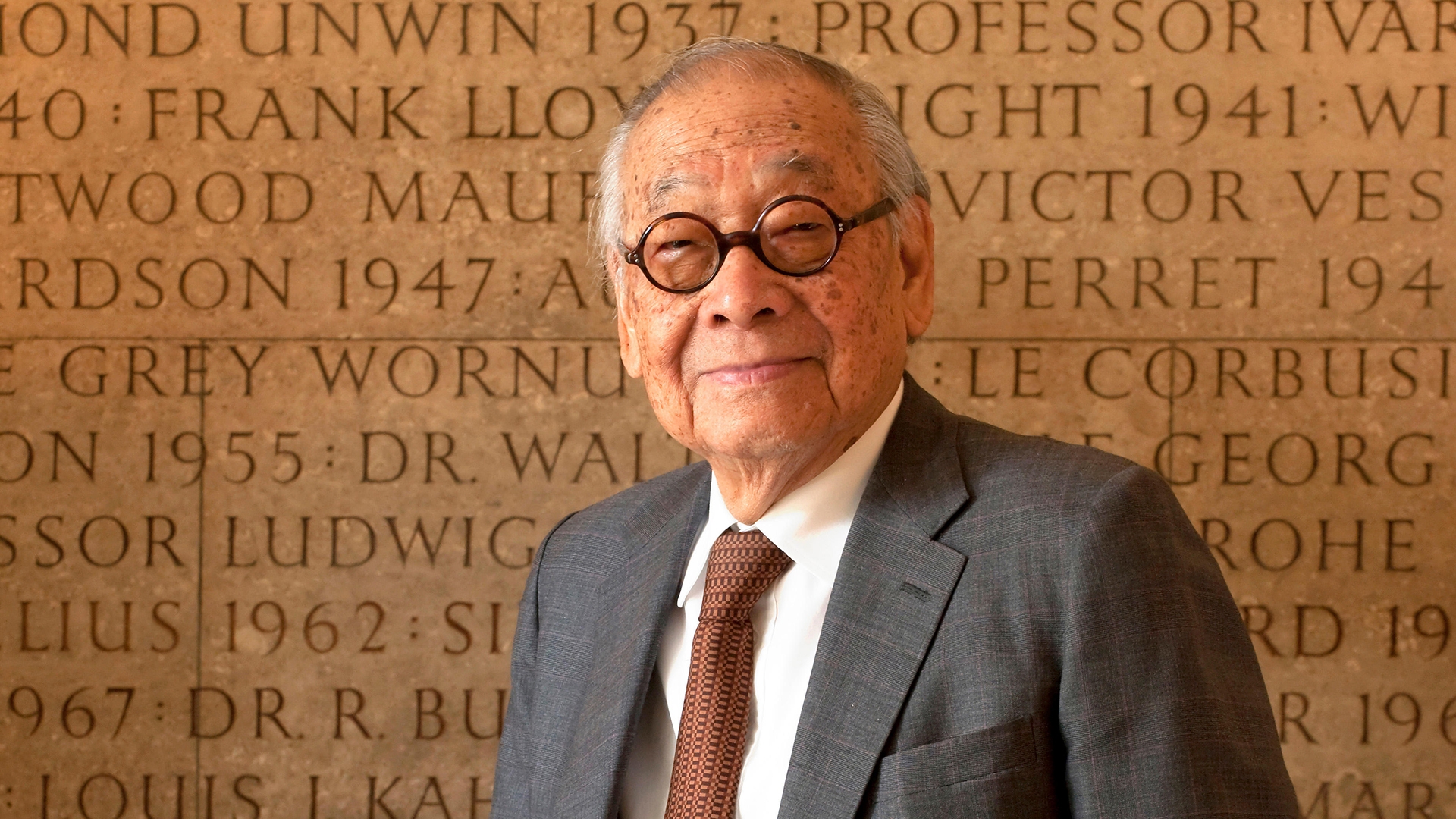

I.M. Pei, the Prolific and Iconic Architect, Is Dead at 102

Article originally appeared on www.architecturaldigest.com by Nick Mafi. Read the full article HERE.

Ieoh Ming (I.M.) Pei—who was born in Guangzhou, China, in 1917, and died yesterday in New York City—left an indelible body of work in the form of modern architecture across the globe. Perhaps best known for his controversial 1989 design of a glass pyramid at the entrance to the Louvre in Paris, Pei had a prolific career in architecture that lasted six decades.

To be sure, each of his buildings redefined any community where they were located. They added name recognition to cities in the Rust Belt, as did his Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York. “Pei was almost singular in his ability to make modern architecture seem classical and timeless,” expresses Michael A. Speaks, professor and dean of the School of Architecture at Syracuse University. “As it turns out, I’m writing this from the Everson Museum this morning, and this feeling of classical modernism permeates every square meter of the building. It has been quite a spiritual experience being here this morning.” At other times, Pei challenged us to consider the materials used in carving out a new art museum. In his 1978 commission to build a new, modern wing of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., Pei was adamant about using the exact same Tennessee marble as American architect John Russell Pope did with his original National Gallery Building of 1941.

But for those who knew him best, Pei’s abilities as an architect paled in comparison to his warmth, affability, and humanity. “I knew him as a humble man, always smiling,” says Santiago Calatrava, architect of the World Trade Center transportation hub in New York City. “A soft character but the possessor of a keen and clear mind.”

“Pei’s standing in the profession is assured—he won every major accolade there is,” says Norman Foster, architect of Apple’s newest campus. The winner of the Pritzker Prize in 1983 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1992, Pei never lost sight of the core values that went into designing powerful works of architecture. “I sat at a dinner with him in Berlin, years ago, where we shared our mutual passion for drawing,” architect Daniel Libeskind reminisces. “You can see in his brilliant buildings a mastery of architecture’s millennial tradition.”

It’s almost become a prerequisite for great architects to be fiercely competitive. And while Pei didn’t fit the part on the surface—soft-spoken, humble, kind, funny—deep below there was a fire burning that fueled him to win commissions that shocked his contemporaries. Perhaps Pei’s greatest trait as an architect was his ability to absorb.

When he was commissioned to design the Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar, Pei was unsure if he should take on the work. A collector of Western art, Pei acknowledged knowing little about Islamic art. Yet he saw it as an opportunity to grow—both as an architect and a person. After reading a biography of the Prophet Muhammad and taking a tour of Islamic architecture around the world, Pei completed the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha in 2008.

But it wasn’t just religion and culture that challenged Pei to break the mold; it was music, too. After being asked to design the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Pei felt initial unease—the architect wasn’t a fan of that genre of music. Yet, ever the curious soul, Pei doubled down, commencing on a trip to several rock concerts with Jann Wenner, the cofounder and publisher of Rolling Stone. Pei completed Cleveland’s iconic Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1995.

The Chinese-born architect knew that with several of his high-profile buildings, such as Paris’s Louvre pyramid and Colorado’s National Center for Atmospheric Research, he had captured lightning in a bottle. Sentiments he expressed influenced a generation of architects after him. “As a student at the University of Washington, I was influenced by I.M. Pei’s amazing Boulder Atmospheric Research Building of 1967,” says American architect Steven Holl. “I loved what Pei later expressed, that three or four masterpieces are more important than 50 or 60 buildings.”

Pei was a vitally important link between modern architects today and the forefathers of modern architecture (Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Saarinen, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Breuer, among others). “I saw him as an architect who carried the baton of modern architecture from one generation to the next, and the message he carried was heard all over the world,” says Calatrava. “His architecture confronted the modern with the classic in an iconic fashion, and through these gestures he elevated a generation of architectural accomplishment to rival that of past masters in a way that many of his contemporaries could not.”

While Pei traveled the world in designing buildings that will undoubtedly stand the test of time, he remained true to his roots of influence in the form of Chinese landscape architecture. “He created uncompromisingly modern designs, but was sensitive to tradition and the value of the vernacular,” explains Foster. “He drew on concepts developed by Chinese landscape architecture, reflecting a deep appreciation of the importance of the spaces between buildings. The integration of nature and landscape into his designs is a theme that runs through much of his work, from early projects such as the Mesa Laboratory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado right through to his later work at the Miho Museum in Japan, which was literally built into the landscape.”

While the world rightfully mourns the loss of this revolutionary architect, one can easily consider the many gifts he has left behind. The built environment is surely richer for the direction in which he steered modern architecture. But the best of Pei’s influence may be yet to come. “He was one of the greats and will be missed, yet he leaves behind a formidable legacy that will continue to influence architects and designers for decades to come,” says Foster.