The youngest in her family by over a decade, Isabel Bishop (1902-1988) was often lonely as a child. She filled her free time drawing and attending Saturday art classes, and after her family relocated from Cincinnati, Ohio to Detroit, Michigan, Bishop began attending the Wicker Art School. A serious student, Bishop first drew from a nude model when she was twelve years old. That she was permitted to attend live figure drawing classes is noteworthy given that in the early twentieth century it was deemed inappropriate for women of any age to work from nude models.

Bishop’s interest in observing people—a passion that would last throughout her career—began in Detroit. Her father’s school administrator salary meant her family straddled the border between two socioeconomic classes. While they lived in a lower-income neighborhood, her parents identified with families who were better off. Remembering her time in Detroit, Bishop explained, “We were very isolated in Detroit and had almost no social life because though we didn’t have the money we identified with the big houses on the next block. I wasn’t supposed to play with the children on my block or be connected with them but I wanted to be.” Bishop directly connected her observations of her Detroit neighbors with depictions of the working class that she later became known for.

Recognizing her artistic talent, a wealthy cousin paid for Bishop to move to New York City. There, Bishop enrolled in the New York School of Applied Design for Women in 1918, studying illustration. After bristling at being instructed in drafting fundamentals given her prior experience, Bishop transferred to the Art Students League of New York to study painting first under modernist painter Max Weber and later under Kenneth Hayes Miller. Miller’s tutelage was important for Bishop, as Miller eventually formed the Fourteenth Street School that Bishop would join alongside painters Reginald Marsh, Raphael Soyer, Moses Soyer, and Edward Lanings. So named for their proximity to Fourteenth Street and Union Square, these artists continued the Ashcan School’s tradition of portraying everyday urban life.

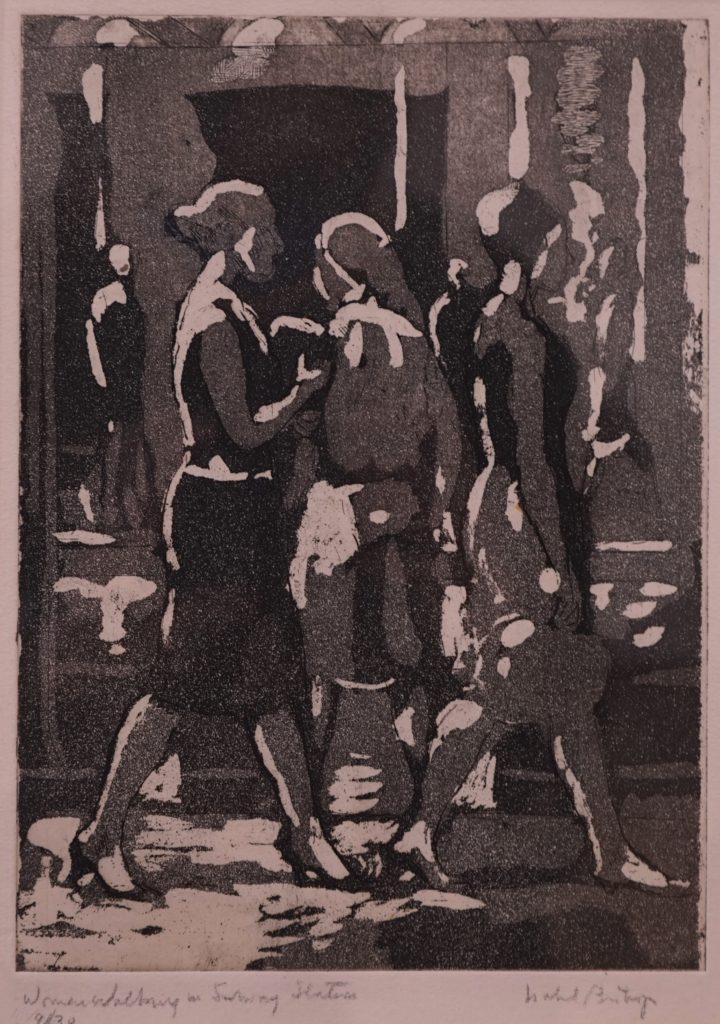

Bishop rejected the long tradition of “heroic” art that venerated rich and powerful people, significant historic moments, and grand ideas. Instead, she focused on the “unheroic,” such as those she watched from her studio on Fourteenth and Union Square. Bishop strove to capture the spark of the everyday with as much naturalism and charisma as possible, evident in the print Women Walking in a Subway Station. She explained, “The subject must seem unmanipulated … as though a piece of life had been sneaked up on, seized, and somehow became art.”

Best known for her kinetic, everyday naturalism, Bishop worked long hours in her studio observing and sketching. Though her figures seem effortless, Bishop labored over multiple drafts to capture a subject’s perfect slouch or distracted expression. She considered her work to have strong Baroque qualities, particularly within the genre etchings of the Dutch Golden Age master Rembrandt van Rijn. Bishop studied his works, as well as those of Peter Paul Rubens, on her visits to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Everything I have tried to do is Baroque,” she said. “The essence of the Baroque style to me is continuity, a seamless web.” Portraying seamless moments of urban working-class women was important to Bishop, as they represented the American drive to achieve upward mobility.

Bishop also strove to uplift and reinvent the female nude, a subject that increasingly fell out of fashion in the mid-century with the increasing interest in abstraction. Bishop shifted the nude model from a passive object to be seen and desired, to a subject with personality, agency, and interiority. Her subjects stretch and twist. These women undress themselves, reach for their discarded clothes, and pick at their nails. Rarely are these models reclined or passively sitting. Bishop wanted her female nude artworks to capture the possibility of change.

In addition to her work as an artist, Bishop held several notable positions within artist organizations. She was elected an Associate Member and Academician of the National Academy of Design; elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters; elected Vice-President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, making Bishop the first woman officer in the institution’s history; elected the Benjamin Franklin Fellow at the Royal Society of Arts, London; and was awarded the National Arts Club Gold Medal of Honor. She also taught for the Art Students League, the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Skowhegan, Maine, and served as a visiting artist at Yale University School of Fine Arts.

In 1984, Bishop became ill and had to retire from her studio to Riverdale, New York, where she passed away in 1988.

Women Walking in a Subway Station is currently on display in the exhibition Forever is Composed of Nows, along with another print by Bishop, Nude Reaching.

—Kelli Fisher, Curatorial Intern

Sources:

- Brockett, “Artists Of The Fourteenth Street School.” Incollect. Last modified July 9, 2014. https://www.incollect.com/articles/artists-of-the-fourteenth-street-school.

- Lewis, Peggy, ed. Paintings by Isabel Bishop, Sculpture by Dorothea Greenbaum. Trenton: New Jersey State Museum, 1970.

- Nemser, Cindy. “Conversation with Isabel Bishop.” Feminist Art Journal 5, no. 1 (April 1, 1976): 14-20. https://jstor.org/stable/community.28036294.

- Sikorra, Raphael. “Miracle of Movement: Isabel Bishop in Union Square.” Women in the Arts (Spring 2009): 26-28.

- Todd, Ellen Wiley. “Isabel Bishop: The Question of Difference.” Smithsonian Studies in American Art 3, no. 4 (1989): 25–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3108989.