SCI-Arc Faculty Zeina Koreitem of MILLIØNS Wins Everson Museum Competition

This article was originally published on January 24, 2020 on SCI-Arch. Read the full article HERE.

MILLIØNS, the Los-Angeles based architecture firm helmed by SCI-Arc faculty Zeina Koreitem with partner John May was recently announced as the winner of an international competition to design the café at the I.M. Pei-designed Everson Museum of Art at Syracuse University in New York. MILLIØNS’s proposal was selected by a jury comprised of design professionals, critics, and museum leadership such as associate curator at MoMA, Sean Anderson, Jing Liu of SO-IL Architects and Aric Chen (Design Miami) from submissions by four semifinalists including FreelandBuck, NATURALBUILD, and Normal Kelley.

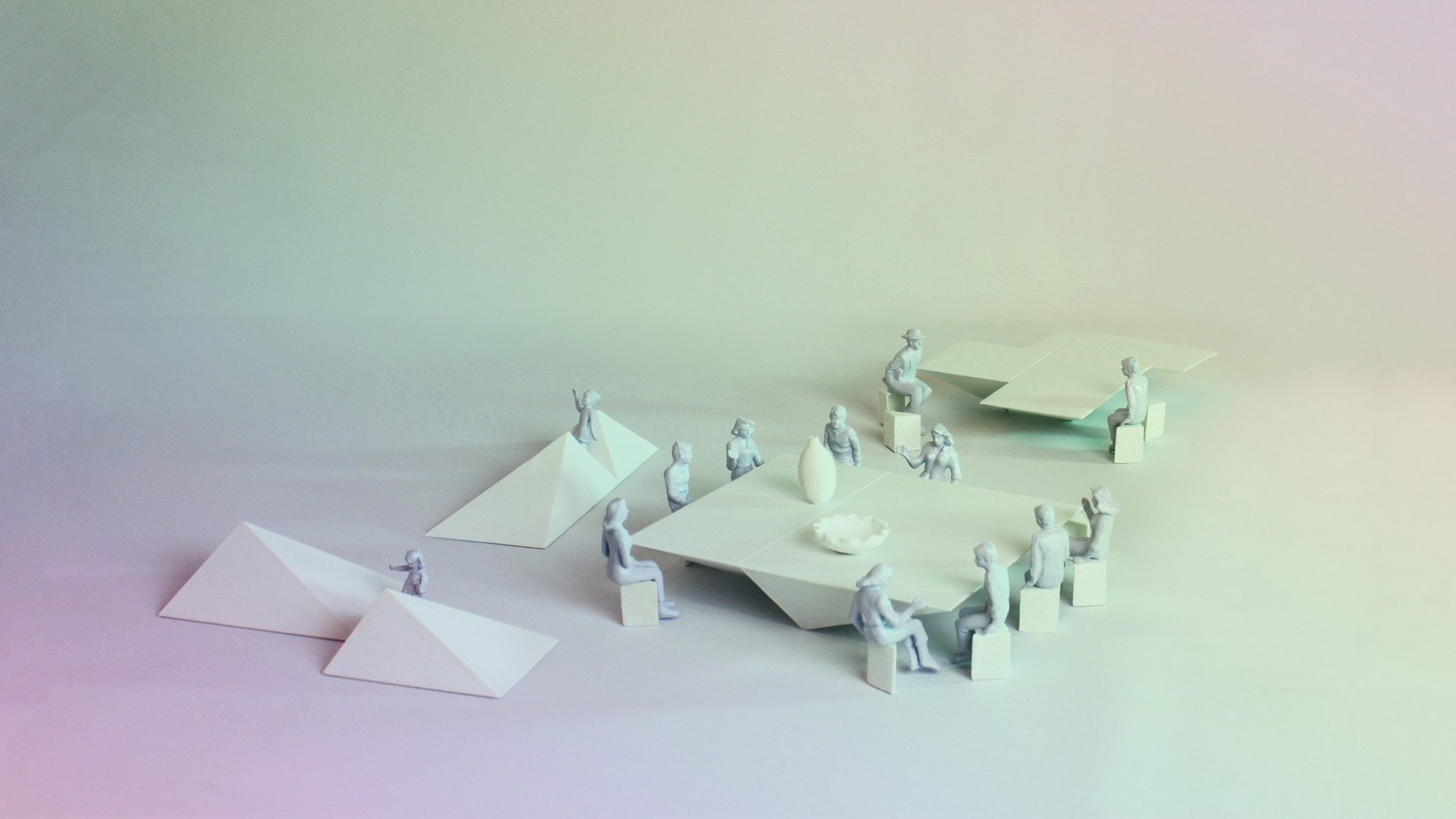

MILLIØNS’s design for the renovated café and event space will feature a double-height display wall of translucent curatorial towers for a rotating selection of works from Dallas-based artist and collector Louise Rosenfield’s donated 3,000-piece functional ceramic collection. The informally arranged open shelving will visually and architecturally merge the museum’s two floors—which are currently separate: an atrium and gallery on the lower level and the café on the upper level. The design rendering also includes a series of inverted pyramids, evoking Pei’s geometric aesthetic, arranged in clusters throughout the atrium space—where visitors will eat and drink from the ceramic artworks.

“MILLIØNS brings a striking individuality to their work,” says Everson Museum Director Elizabeth Dunbar. “Their approach to the café design within I.M. Pei’s iconic Everson brings to mind Pei’s own daring intervention into the Louvre. MILLIØNS included prismatic glass towers in their design, brilliantly combining function with architectural flair and conceptual rigor. They not only thoughtfully engage Pei’s style; they have highlighted its unique characteristics while simultaneously giving Louise’s collection the prominence and respect it deserves. We are all so very excited to work on this project with MILLIØNS. Together we are creating a café space and experience unlike any other in the world.”

SCI-Arc initiated a conversation with Koreitem about the project.

SCI-Arc: Hello Zeina! Thanks for taking the time to speak with us. To start with, would you like to share a few words about the experience of participating in this competition?

Zeina Koreitem: Thank you Sally. There are a number of things that made this competition really interesting for us. First, the Everson Museum of Art itself is a canonical building, designed by I.M. Pei—one of his earliest institutional buildings and his first built museum. Also coincidently, one of our favorites! We love the raw concrete finish and we love the massing. Second, this competition coincided with I.M. Pei’s passing away this past year, as well as the fiftieth anniversary of the museum. So a number of important events aligned. Finally, the ceramics collection, around which the competition was organized, is an incredibly rich and beautiful family of objects, and the donor Louise Rosenfield had a very particular vision for how the collection would be integrated in the museum. I would like to also add that the competition was organized in very unique way—unlike typical institutional competitions, young emerging practices were invited to compete in the first round; the four finalists were then compensated with a generous budget to develop their final proposals. And of course, unlike most “ideas” competitions, this one will be built! We’ve had a really amazing experience so far and are looking forward to working with everyone involved. Competitions of this type have become exceedingly rare in the US.

Can you talk about the Louise Rosenfield’s collection factored into the design brief?

[Dallas-based collector and artist] Louise Rosenfield has amassed an eclectic collection of functional ceramics by mostly contemporary American artists. When she donated her 3,000+ pieces to the Everson Museum, her one rule was that the pieces must be used—not only displayed—which is really a very radical position for a collector. A couple of years ago, Louise envisioned the collection going “to a restaurant [where] it would be used until it’s all broken, except for the last piece.” That last object, she imagined, “could go to some archive or some historical place to tell the story of the Rosenfield collection.” So the competition was rooted in this idea that Louise’s objects would be used in a new restaurant, to be built in the west wing of the museum. The museum has a plan for a multi-phased renovation of the entire West Wing, but this café became the priority because of [Rosenfield’s] donation.

What can you say about the space itself and how that dictated the decisions you made with regards to this design renovation? Was there anything about the space that presented a design challenge?

This radical idea of “use” in the context of a museum fueled the brief of the competition, and for us this meant an unusual approach to art curation and art display. When we began researching the collection, it became obvious to us that to dissociate ceramics from their use is to detach them from their cultural meaning. We also learned that the glazes used on the pieces in Louise’s collection, and the way they are fired, makes them resistant to damage under UV light. This was an important discovery for a few reasons. This area of the museum—the way I.M. Pei conceived of it— was not meant to be an exhibition space, nor was it meant for public access.

In essence, there are a couple of different spatial conditions that make it very challenging to introduce a collection of this caliber and size into the space. First, the height of the ceiling and the natural light condition, which is beautiful, but not favorable for object display, or for any type of curatorial project. The space is currently only naturally lit from a narrow light well above which produces a kind of chiaroscuro effect in the space, a strong contrast between light and dark, almost pitch-dark at times. So we proposed to insert a series of glass towers, which act simultaneously as storage, display and, through prismatics, as “light machines” that can refract and reflect light into the deep space of the café—essentially capturing the light from the skylights are magnifying and reflecting it horizontally into the proposed café space.

At the same time, there is currently no direct access for the public into the lower level of the west wing, but it seemed like an obvious space in which to house this new collection. So we took these two major challenges into consideration and introduced diffused ambient light in the space, such that it will now act as both a café and, on the lower level, a new ceramics gallery (in the double-height atrium space).

Can you discuss how you came up with a design brief using these materials?

We researched ceramics, communal food cultures, prismatic glass, and natural light. We found incredible construction photos of the Everson Museum in 1965, where we discovered that Pei’s sculptural massing techniques had produced the aforementioned intense chiaroscuro effect in many spaces, which was intentional, but was also a consequence of the fact that concrete absorbs so much light. We became fascinated with the idea of an infinitely thin intervention that would have a drastic atmospheric effect. Hence, the prismatic glass, which itself will have a very delicate presence in the space, but will produce enormous atmospheric effects.

What about the elements of use? Will visitors actually be able to utilize the ceramic pieces displayed?

The curatorial towers, which we also refer to as the “prismatic machines,” will be open display cases. Any visitor can reach out, pick a piece to drink from or eat from. Visitors could also pick, at the point of purchase, teas or coffees that are only served in specific pots and vice versa. What became interesting for us is the process and space of maintenance; the handling and cleaning of these pieces. We imagined it as part of the dining experience—as a kind of performance. In our proposal, the Front of House and Back of House of the museum coexist in what we called the “Demonstration Gallery” across from the café.

How else does the curatorial drive of the institution dictate the choices you’ve made for this design?

The brief was in some ways difficult to approach. We were asked to intervene in three separate spaces, two interiors and one exterior: the café, the gallery, and the vestibule and bridge. We began to conceive of a family of elements that could serve as “curatorial surfaces,” both horizontal and vertical. In the end, what we proposed is a kind of loose assemblage of discrete elements, which provide flexible surfaces for curation and communality.

Can you describe the furniture you’ve created for the space, as well as the concept and materials behind those choices?

The main furniture elements aside from the curatorial towers are the tables—which we referred to as the “Moveable Feast.” The tables are meant to bring the ceramic pieces into the open. When arranged as a family on the tables, the ceramic pieces become sculptural objects rather than functional objects. The tables are inverted pyramids that can be combined to form larger horizontal surfaces if needed. There are four unit types or different angles ranging from 4’x4’ to 7’x 6’. We designed the tables in such a way that a minimum of three have to be joined in order to be in equilibrium. The tables are also intentionally too deep, so that the curators can display pieces in the center, beyond arm’s reach. Facilitating that kind of interweaving of curation and communality was something that we felt was valuable when we researched the history of ceramics.

What other elements will be featured and what were the decision making processes like for those?

The elements are the glass Curatorial Towers (the “prismatic machines”), the lightweight Moveable Feast tables, and the concrete Demonstration Gallery podiums, which will be used for curation and real time demonstration events. There are other materials and strategies that will intensify and redirect light into some of the darker spaces, but these are the three primary elements.

What are the most exciting parts about this project to you?

The Everson Museum of Art is our favorite I.M. Pei project, so being part of its revitalization is very exciting. We are also excited about Louise’s radical mandate that her collection be used, which opened the project up to topics we have always engaged in our practice—communality, events, and public life. This is an opportunity to test them on a much larger scale.

When do you start? What are you most looking forward to about this project?

Construction begins in the summer of 2020. I am looking forward to seeing it realized!

—

Zeina Koreitem is founding partner, with John May, of MILLIØNS, a Los Angeles-based design practice. She is design faculty at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) in Los Angeles. Previously she has held positions as Design Critic in Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and taught at the University of Toronto and USC School of Architecture. Koreitem has previously worked in the offices of Dominique Perrault Architecture in Paris, and Pritzker winners RCR Arquitectes in Olot, Spain. Her writings on computational color, computer graphics, and communality have been published in Project Journal, e-flux, and Harvard Design Magazine. Koreitem holds a B.Arch from the American University of Beirut, where she received the AREEN Project Award of Excellence in Architecture, and the Outstanding Creative Achievement Award; an M.Arch 2 from the University of Toronto; and an MDes in Design Computation from Harvard GSD, where she received the Daniel L. Schodek Award for Technology.

MILLIØNS’ recent work includes completed and ongoing projects in California, New York, Boston, Germany, and Beirut. Recently selected as the winner of an international competition to reimagine the west wing of I.M. Pei’s Everson Museum, in Syracuse, NY. MILLIØNS’ experimental work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions at Friedman Benda Gallery, the Storefront for Art and Architecture, The Architecture + Design Museum of Los Angeles, and Jai & Jai Los Angeles, among others. Their essays and work have appeared in Harvard Design Magazine, Flaunt Magazine, I.D., a+t, Dezeen, Architect’s Newspaper, and in a catalog of their work on experimental collective living, New Massings for New Masses: Collectivity After Orthography